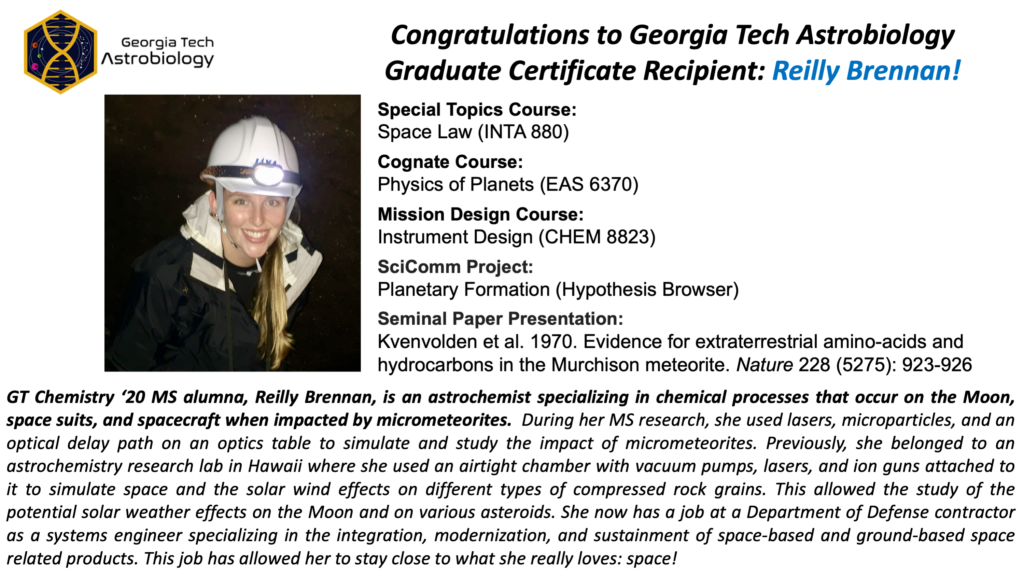

Please join us in congratulating Reilly Brennan, 2020 recipient of a GT Astrobiology Graduate Certificate and GT Chemistry MS ’20 graduate!

Read Reilly’s sci comm project here.

Please join us in congratulating Reilly Brennan, 2020 recipient of a GT Astrobiology Graduate Certificate and GT Chemistry MS ’20 graduate!

Read Reilly’s sci comm project here.

Brief summary: The very first “ocean life detection” mission took place on board the HMS Challenger in 1872, as it set out to establish the existence of life at the deepest ocean depths. Scientists and crew sailed for four years collecting chemical, geological and biological samples from the far reaches of our world, and produced to first comprehensive survey of Earth’s ocean – from sea surface to sea floor. Today, scientists explore the ocean through a combination of human-operated and autonomous instruments. The technological landscape is changing at an unprecedented rate. Space scientists are also rapidly developing technologies required for missions to other worlds, including ocean worlds, despite the striking difference in the resources invested in ocean versus space science instrumentation. Our laboratory focuses on better understanding how matter/enery flow between the biosphere and the lithosphere. To that end, we develop technologies that help further our understand of these relationships, both in the ocean and on land.

We are, however, also committed to democratizing science by developing modular, open-design vehicle and sensor platforms that allow inexpensive commercial sensors (as well more bespoke emerging technologies) to be easily deployed on deep-sea missions. Here I will present some of the latest developments -as well as the lessons- from exploring our own inner space. We will also present our data from recent efforts aimed at examining the relationships among abiotic and biological processes in our ocean. These technologies and methods can help us unlock the mysteries of the cosmos, in particular that enduring question of whether life exists on other celestial bodies. We posit that fostering a rich and extensive collaboration among ocean and space scientists is critical if we are to advance our understanding of other ocean worlds, such as Enceladus and Europa, beyond the scope of current missions and technologies.”

The Europa Clipper mission will be able to measure volatile CO2 isotopes of Europa’s plumes and exosphere—but what can those measurements tell us about the surface ice or subsurface ocean? Our laboratory experiments interact an initial gaseous CO2 (that may be sourced from water-rock interactions at the seafloor) with various seawaters, and measure the resulting CO2 to determine what changes take place as a result of this interaction. Isotopes of CO2 from low pH systems do not show a substantial change for carbon, suggesting that carbon isotopes from a low pH Europa will reflect the original CO2.

However, alkaline (high pH) systems similar to Enceladus or a high-pH Europa show a large variability in carbon isotopes that is due to varying carbonate speciation. We use our laboratory spectra as a ‘training’ dataset for machine learning. Our preliminary work demonstrates that ‘supervised’ training of metadata and data from these spectra form clusters based on the concentration of CO2 and the composition of the seawater, and is therefore promising for future interpretation of CO2 mass spectra using predictive algorithms.

Please read this new Nature Astronomy paper to prepare for the discussion.

A microscope for life detection is a top candidate instrument for ocean world and other planetary missions. Microscopes developed for ocean, earth, and space exploration have significant overlap; with analog terrestrial environments offering excellent settings to test techniques potential for space application.

In this talk I will introduce basic principles of microscopic imaging and discuss the application of microscopes for life detection and environmental exploration. I will then present several different microscopic imaging systems developed for both oceanographic exploration and planetary missions. This will include details on a submersible digital holographic microscope (DHM) being developed for the underwater robot Icefin, results from benthic underwater microscopes used to observe seafloor organisms, and towed systems for imaging plankton. At then end of this talk I hope you will have a better understanding of the capabilities of microscopes, their history of use in space and ocean applications, and future potential.